“There is a big difference between a satisfied customer and a loyal customer.”

Shep Hyken

Recently Marketing Workshop, as part of a larger project, conducted a quasi-depravation exercise to understand an element of brand loyalty. A tactic employed in the research design also delivered useful learning for the client’s product evolution team, that being, insights about how consumers resolve through replacement or otherwise when in a situation of not having a typical resource available, your resource. As you might imagine, therein lies indicators of opportunistic gaps. “What do they use (buy) when they don’t use (buy) mine?” In our study, we asked respondents to imagine a scenario where they awoke to find their favorite mobile app had disappeared—forever. Respondents submitted short selfie videos of themselves walking us through how they’d feel knowing the app had gone to the great trash folder in the sky, and what next.

The reactions were visceral; you could actually see respondents squirm as they imagined a life without Facebook or Waze or YouTube or Marco Polo or whatever. In front of our eyes, you could see them racing through several of the seven stages of grief, beginning with “shock and denial,” “depression” and then, ultimately, “acceptance and hope.” Of course, no one (thankfully) was bawling, tearing their hair out or screaming “why me?!” over and over again. This was, after all, a giant “what if,” and we were talking about an app, not a loved one. What’s more is, in this particular scenario, there’s actually an eighth step—finding a replacement.

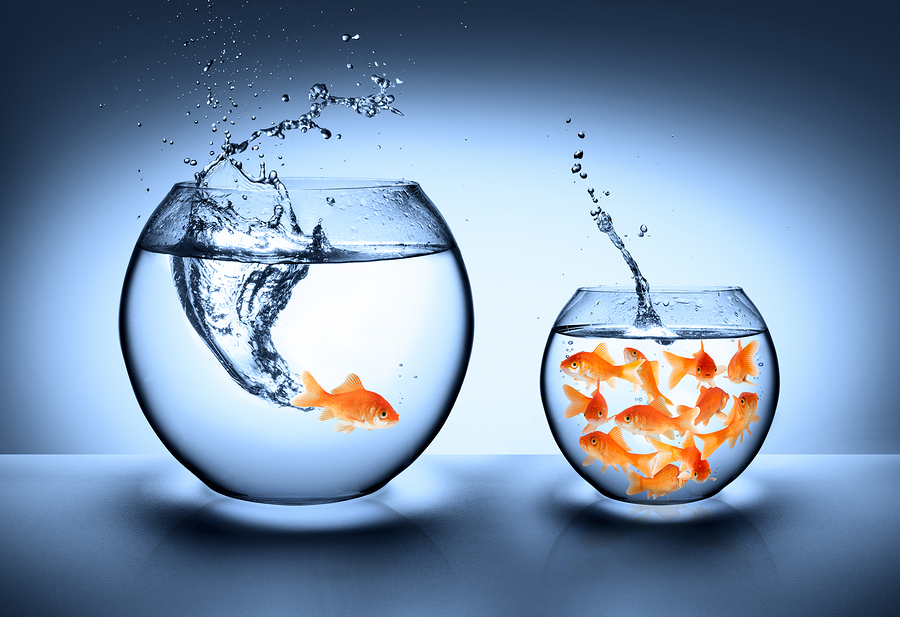

Unlike a loved one, there is always an alternative when it comes to an app, hamburger, hairspray or hoodie, and finding it isn’t particularly difficult. So, when anyone says “there is no brand loyalty,” they’re not all wrong and they’re not all right, either—there’s simply varying degrees of it.

For example, some recent primary data revealed that, among young people between 13 and 39 years old, the highest ratio of usage-to-self-reported-loyalty was in the technology and entertainment category, inclusive of brands like YouTube, Disney and Microsoft. For that category, the ratio of usage to self-reported loyalty is about 3-to-2, while for CPG it’s only around 2-to-1. Without getting into the granularity of each category—because that’s a much longer blog—you can ascribe more brand loyalty to tech and entertainment, because there’s a greater time investment placed in those brands and, when it comes to social media, consumers have equity in those brands. But, for CPG, consumables are a means to an end—many food products are similar, and have similar prices, packaging and health benefits.

All that said, there’s no consensus on what generation is the most loyal; recently, eMarketer revealed that Generation X earns top honors, while Elite Daily says no generation is more loyal than Millennials.

So, the short answer is there is brand loyalty, but loyalty isn’t binding. It simply means it may be harder to replace some brands than it would others, but it is possible, especially in categories where favorite brands are more easily mimicked. Which also begs these questions: Can loyalty be bought and how do rewards promote a false loyalty—a you-scratch-my-back-and-I’ll-scratch-yours loyalty rather than a heartfelt one? It makes us remember what Dwight Schrute, the nerdy assistant to the regional manager on “The Office,” said it best when he asked about loyalty to his employer, Dunder Mifflin: “Look, I’m all about loyalty,” he said. “In fact, I feel like part of what I’m being paid for here is my loyalty. But if there were somewhere else that valued loyalty more highly, I’m going wherever they value loyalty the most.”

~ Marketing Workshop